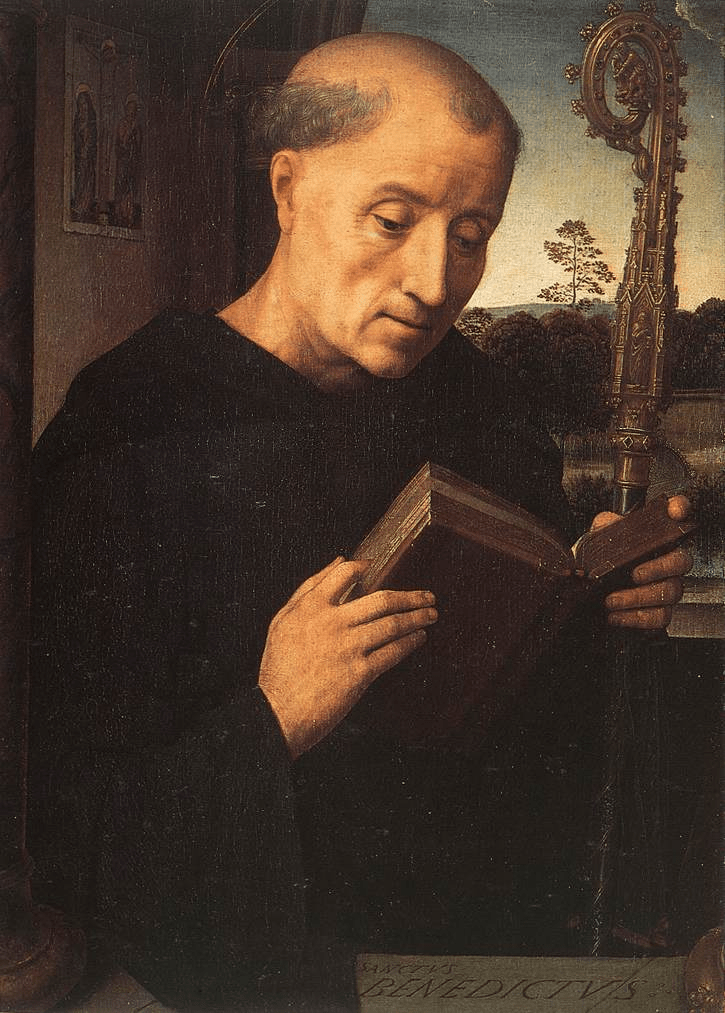

Benedict was born into a well-to-do, Christian family in Nursia, Italy, around the year 480 and was sent to Rome to be educated when he was a teenager. He was revolted by the immoral behavior he saw there, so he quickly left Rome with his nurse (a caregiver-turned-housekeeper) to live a life of solitude in the mountains. Soon he realized that God was calling him to an even greater abandonment of the world. While he was searching for a place to live in complete solitude, he settled on the city of Subiaco, where he met a monk named Romanus. Romanus brought bread to Benedict every day (disobeying the monastery’s rules), while he lived in a nearby cave for three years. When other men found out about Benedict’s holiness and simple way of life, they wanted to follow him. Benedict settled the men who wanted to be his disciples into twelve separate monasteries, with twelve monks in each. Unfortunately, the monks began to resent him, and they even tried to poison him. (Benedict later decided that he had been too severe with them.) When the cup they tried to poison him with broke after he had blessed it, he recognized what they’d tried to do. He repented of his past severity with them and left them suddenly. He moved to Monte Cassino, the site of a former pagan temple, and around the year 530, he and those who followed him began to build a monastery. This ultimately became one of the greatest monasteries that the world has ever known. Learning from his experiences at Subiaco, Benedict gathered all his monks into one monastery, developed his famous rule for monastic life, and established the practice of ora et labora among his monks, in which they lived a structured life of both prayer and work. He cared for the sick people who lived outside the monastery and the poor who came to the monastery for alms and food. Benedict died in the year 547 as he stood in the monastery’s chapel, with this arms supported by his brothers and his hands lifted up to Heaven.